Have you ever wondered why some spaces feel immediately inviting, while others leave us cold or even uneasy? Traditionally, these emotional responses have been hard to quantify or predict—until now.

At AAIRL, we’re excited to spotlight a compelling step forward in architectural design, led by a collaboration between Gal Guz, Nikolas Martelaro, Gerhard Schubert, and myself. Our new research paper, “Quantifying Architectural Experience Using Visual Language Models: Does AI Dream of Rendered Spaces?”, asks a fascinating question: Can advanced AI models predict how humans will emotionally respond to a space, even before it’s built?

Architecture has long depended on measurements: dimensions, materials, light. But translating the emotional impact of a space (“Is this cozy? Stimulating? Overwhelming?”) into numbers has been elusive. Each person feels space differently, which makes universal design both crucial and challenging.

However, recent breakthroughs in large language models (LLMs) and visual language models (VLMs), like GPT-4o, open up the ability to “simulate” human experience. Imagine building not just physical models, but digital synthetic humans who can “walk” through your designs and tell you how they feel!

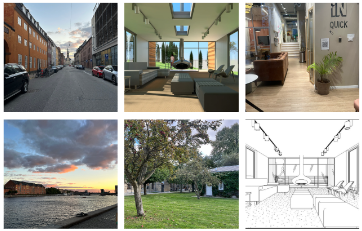

The Experiment: AI vs. Human Feelings: We put GPT-4o’s vision-to-emotion prowess to the test. We gathered 10 images of different spaces and asked human and AI to completed emotional ratings using the well-known PANAS scale, how each image made them feel (20 different emotions).

We found out:

- Strong Negative Intuition: GPT-4o’s negative emotion ratings strongly matched humans—an R² value of 0.79, rising to 0.8 after filtering out CAD images. In other words, AI was excellent at predicting spaces that felt distressing or unpleasant.

- Positive Emotions—More Subtle: The correlation for positive emotions was moderate overall (R² = 0.13), but improved to a “strong” connection (R² = 0.53) after removing the CAD images. Curiously, the AI tended to overrate positive feelings in highly artificial (CAD) spaces, whereas humans rated them much lower.

- Fine-Grained Emotions: For most individual negative emotions (afraid, upset, nervous, etc.), correlations between AI and human scores were high across the images (see Table 2 on page 9). Positive emotions were less reliably predicted, with ‘inspired,’ ‘proud,’ and ‘interested’ best reflected.

This work hints at a revolutionary future in design:

- AI as a Smart Design Companion: Instead of relying solely on personal skill and intuition, architects can now lean on AI to “pre-screen” how their designs might make users feel.

- Quantitative Emotional Metrics: Emotional experience becomes as quantifiable as daylight, circulation, or material use.

- Optimization: With more refined AI models, it’s conceivable that design processes could optimize space not just for cost or efficiency, but for positive emotional impact.

This methodology could pave the way for large-scale studies on emotional response to the built environment—including cultural or demographic adjustment.

This research shows real promise: AI can now help us measure and maybe someday optimize the feelings our spaces create. If “form follows function,” perhaps now it can also follow feeling.

We at AAIRL are eager to see how these tools empower more human-centric architecture—making the intangible, finally, a little more measurable.

Original paper on ResearchGate